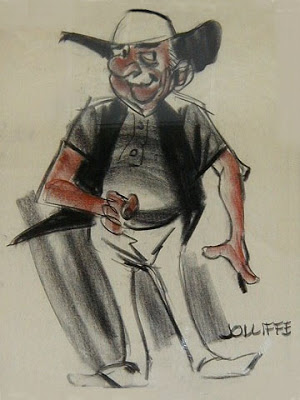

A Whiff of Jolliffe

Eric Jolliffe (1907 – 2001) – Australian cartoonist and Spearfisher.

PARLIAMENT would work better if shifted to Bungendore show-ground. This is the conviction of Eric Jolliffe, the nation’s best-loved bush cartoonist. Viewing the ACT and near-NSW, he has entered the new-home-for Parliament debate.

PARLIAMENT would work better if shifted to Bungendore show-ground. This is the conviction of Eric Jolliffe, the nation’s best-loved bush cartoonist. Viewing the ACT and near-NSW, he has entered the new-home-for Parliament debate.

Moving the politicians to the show paddocks at Bungendore would help fix the deficit, and contribute to open government, he says. Parliament House could be leased for the factory functions for which it seems to have been designed. If the locals would allow it, Bungendore facilities would be ideal for politics when not needed for the local show. They could be endlessly added to with bush materials at low cost”, the artist says. Dashes of stringybark architecture would lend Parliament a new tone, of appeal to tourists. Snug Party rooms could be knocked up from corrugated iron. What better for the non-members’ bar – the most stimulating part of either House – than an open-air beer stand? Cabinet could sit in the shearing pavilion, especially on mini-Budgets. Back-benchers with slenderer majorities would want the run of the grandstand. Reciprocally, the change would lend financial balance to the Bungendore Show Society, through the turnstiles . . .

Working seven days weekly at a youngish 72, for the love of it as much as anything, Jolliffe knows most of rural Australia, including Canberra’s environs. Country communities know him, too, as a lecturer on cultural conservation as well as creator of long suffering scrubland black-and-white identities like Sandy Blight, Andy, Saltbush Bill, the Witchetty Tribe and Callaghan’s Kids.

Working seven days weekly at a youngish 72, for the love of it as much as anything, Jolliffe knows most of rural Australia, including Canberra’s environs. Country communities know him, too, as a lecturer on cultural conservation as well as creator of long suffering scrubland black-and-white identities like Sandy Blight, Andy, Saltbush Bill, the Witchetty Tribe and Callaghan’s Kids.

Constantly travelling, he holds district hall audiences’ attention with earthy oratory, and rolls them in the uncarpetcd aisles with poker faced wit. Like his artwork, it is dead-pan and laconic. Lightning sketches have become part of his act. For bets he has taken it before the toughest city club crowds metropolitan promoters could name, and silenced the poker machines by the hour.

For half a century a freelance except for a brief staff job on Smith’s Weekly in Sydney, he is recalled by that legendary newspaper’s historian, George Blaikie:

Eric joined us in 1944 on his march to glory … He had humped the bluey and toiled at all kinds of farm and station jobs. Wherever he went he sketched the minutiae most people failed to see – shacks and sheds, funny old gates and tree stumps they hinged on, bark roofs, billabongs and cows in bogs.

Such authentic reference was poured into his gags and he became our most brilliant interpreter of the countryside.

Saltbush Bill

His originality unsurpassed, Jolliffe tramps in harness with a legendary legion from the heights of black-and-white greatness: Stan Cross, Virgil Reilly, Joe Jonsson, Alex King, Jim Russell, Joan Morrison, Alec Gurney, Jean Cullen, Bert Smith, Mollie Horseman, Emile Mercier, Norm Mitchell, Les Dixon, Norman Rice, Rosaleen Nor-ton, George Finey, Walter Pidgeon, Bruce Begg, Lex Bell, Jack Quayle, Cec Hartt, Lance Driffield, George Donaldson, Frank Dunne, Syd Miller.

Those generations of illustrators tended to be all-rounders. Jack-of-all-trades artists like Jack Lusby and Les Such, with whom Jolliffe shared a studio for a period, left marks also as short story writers and Jolliffe is a knockabout craftsman as well with a typewriter.

Colour which cartoonists then splashed on newspaper pages has been mostly faded in the modern world of mechanisation, conformity, syndication, altered tastes and hurry-up lifestyles. Jolliffe, the survivor, has changed none of his painstaking methods, his output over the last generation or so appearing largely in his distinctive ‘Outback’ periodicals, of which there have been more than 100.

More businesslike than most artists – “if you aren’t you go under; it’s as simple as that” – he prints and distributes ‘Jolliffe’s Outback’ himself. Editions sell in all corners of the continent he scours for ideas, and are popular in other countries.

Living quietly in his Sydney studio-home, rarely personally publicised and very much his own man in a corporate world, his individuality has kept him out of political cartooning.

I envy artists who can make politicians figures of fun, he says. I couldn’t. I’d be too savage. On all of ’em.

So his fascination for Australia does not extend to its political machinery with its cogs and gritty wheels within wheels.

Nor has Jolliffe ever lampooned anyone cruelly. There is, however, a practical policy message:

Among the world’s best, Australia’s black-and-white art has been strangled by syndication. Swamping in from the USA and elsewhere, cheap foreign material has killed our profession. Only a handful of political cartoonists, editorialising, make a reasonable living now; the gag-man, the strip cartoonist, works only part time or has been squeezed out, or lives at the poverty level. If it were butter, coal, steel, TV sets or tinned mutton, pouring in, the Government would whack on import duties to protect home industry. But it sells artists down the drain. Few young people are coming into the game any more. They have to go for commercial art, advertising and so on. If the Government knew its business, it could secure a bit of public revenue in the name of a once flourishing, highly individualistic, now virtually defunct, art from in this country.

The king of comic Australiana is by birth an Englishman. Son of a Portsmouth carpenter, he claims he became an instant Australian on arrival in Perth, aged four years.

The king of comic Australiana is by birth an Englishman. Son of a Portsmouth carpenter, he claims he became an instant Australian on arrival in Perth, aged four years.

Among the youngest of a large family, he went to school in Balmain, Sydney, learning the three R’s in the cane-and-slate style around World War I, and went bush at 16. This gave him first insights into the lives of slab-hut dairymen and pig farmers, timber-cutters and teamsters, drovers and sheep and cattle station characters, country towns folk and whiskered dingo trappers, shearers and road-workers.

Typically, I landed a job on a central western dairy farm where the boss hated cows and used to whale the daylights out of ’em, he says. He had the world’s first milking machine, and it used to roar and backfire and hiss sparks and smoke, shake and tremble, and the cattle were terrified and so was I, and the farmer would scream and rage, and all the time the cows were scouring from beautiful Belabula River flats lucerne. Townships were still full of horsemen and buggies and wagons. Country populations were larger and there were few cars. It was Paterson and Lawson and Gordon and Daley and Ogilvie and Kendall come to life for me.

Eventually I acquired a T-model Ford with as much character as any horse. In the end it had only one gear left – reverse. When it came time to pass it on to a new owner I delivered it backwards, with all the dust in my eyes.

Roving from Walgett to Cowra, Canowindra and Coonamble, up into Queensland and down south of the Murray, Jolliffe felt a need to write and sketch for his own amusement.

Back in Sydney from a rabbit skinning contract, he casually enrolled in an art course.

At tech, teachers told me to get back to the rabbits, he says. I was older than other students, and awkward through having been belted at school into using my right hand when I was naturally left handed. Tech was packed with kids in the Depression, and teachers had no time for an older chap like me they thought was wasting their time. School conformity had even extended to forcing kids to all write the same, and with the ‘right’ hand. When it came to serious artwork I found that hand just would not perform the curves, would not make the lines and shades. I reverted. I had to.

Today he writes right-handed while the left does the drawing.

In the depressed early 1930s, Eric Jolliffe wed his accountant wife, May. They had £30 and he earned 10 shillings a gag from the papers. From the outset he earned a reputation as a gifted gag-man, in early days taking his place easily alongside technically more experienced penmen on the strength of his bushy originality and sheer humour.

Nobody else ever had to write, Jolliffe’s gags, something that could not be said for some leading newspaper and magazine artists then. Mrs Jolliffe says the £30 did not last long. “Eric was open-handed”, she recalls. Today she insists on doing most of the driving when her husband is on back-blocks walkabouts.

Always looking around admiring haysheds and roadside mail boxes, outside toilets and old drays and wagons, he could put us up a gumtree! May says.

Their daughter, Margaret, and her husband, Ken Emerson, are artists, while a granddaughter, Jane, 15, tends that way also. All meet up in the Jolliffe studio in his Sydney home overlooking miles of seascape. Festooned with memorabilia, it is a happily disordered museum of old books and mounted butterflies, scrub hats and buffalo horns; a fly-paper recipe is pinned to a wall among letters and cuttings and ancient photographs, and a dingo trap rests in a giant turtle shell.

Creative people have described life in various ways: a farce, tragedy, human comedy, string of circumstantial errors, purgatory or dream. To Jolliffe, it is a leg-pull; like his cartoons and his conversation, he looks you straight in the eye and tells a whopping story without a single grin or groan!

Creative people have described life in various ways: a farce, tragedy, human comedy, string of circumstantial errors, purgatory or dream. To Jolliffe, it is a leg-pull; like his cartoons and his conversation, he looks you straight in the eye and tells a whopping story without a single grin or groan!

Expression of the deadpan gag is the challenge. It is uniquely Australian, like the inland itself. Only in the deep bush can you go into a shanty and find it literally impossible to tell whether your neighbour at the bar has $10 million or nothing. Urban Australia is little different from many other countries; inland, it is unique. In getting this down on paper, remoteness comes into it, pathos, earthiness, country style wisdom. There is the search for freedom which keeps men and women on the land, cheerfully facing risks of seasons, pests, markets and fires and floods which would horrify city businessmen. Maybe it’s all an illusion, but the feeling is there. And you have to seek out the drama of the bush, for there you find the action. Authenticity is just as vital. You can’t go straight for humour and miss out on detail and atmosphere.

Jolliffe drawings are strong on movement. Dissatisfied with the flat, static nature of some cartoons of the 1930s – farmers leaning on a fence, taking part in some dreary exchange of dubious humour – he set himself the task of capturing action.

Ideally, the joke was in the drawing, with no caption needed. Captions had to be terse and true-to-life, too. He will still sometimes deliberate for days over their working, as he carries on inking-in the artwork.

Originally more attracted to writing than drawing, Jolliffe has added commentaries and, more recently, photographs to his ‘Outback’ publications.

His prose has a campfire lilt:

George Joy, Melville Island, was the best bush cook I ever knew -an expert on flying fox, wallaby, turtle meat and eggs. . or: The crocodile is our most dangerous predator, and is also the largest amount of bush meat on four legs, consistently hunted by Aborigines…

How many athletics fans have heard of the Aboriginal Olympics? Jolliffe reports, photographs and sketches them, at Yuendumu, Central Australia – 2,000 men, women and children annually locked in intertribal sporting contests.

How many athletics fans have heard of the Aboriginal Olympics? Jolliffe reports, photographs and sketches them, at Yuendumu, Central Australia – 2,000 men, women and children annually locked in intertribal sporting contests.

Ranging from the opal fields of Lightning Ridge and Andamooka to fettlers’ and timber camps, he writes of boabs and bark canoes, white ants, “neither white, nor ants” -and how to live off the sea, build a pole home, a smoke-house, a fish trap.

Ghost towns he takes readers to include Silverton, back of Broken Hill, where the cattle magnate, Kidman, sold a share of the fabulously wealthy mine for six steers; Gwalia, north of Kalgoorlie, an old gold township made entirely of corrugated iron; and other desert places where the inhabitants live underground, like moles.

Ghost towns he takes readers to include Silverton, back of Broken Hill, where the cattle magnate, Kidman, sold a share of the fabulously wealthy mine for six steers; Gwalia, north of Kalgoorlie, an old gold township made entirely of corrugated iron; and other desert places where the inhabitants live underground, like moles.

Aborigines figure largely in the unusual periodicals and Jolliffe is proud to number hundreds, among his friends, fans and readers. Sensitivity without sentiment describes his approach to them, from Arnhem Land reserves to the stock camps and dusty interior townships of all mainland States. On the lighter side he originated the Aborigine pin-up; in other moods he sponsors Aboriginal theatre, dancing, painting, crafts.

Aborigines figure largely in the unusual periodicals and Jolliffe is proud to number hundreds, among his friends, fans and readers. Sensitivity without sentiment describes his approach to them, from Arnhem Land reserves to the stock camps and dusty interior townships of all mainland States. On the lighter side he originated the Aborigine pin-up; in other moods he sponsors Aboriginal theatre, dancing, painting, crafts.

Let’s not forget that their art forms are far from dying, he says. There is tremendous enthusiasm for them. Their paintings sell like hot cakes inside Australia and overseas.

THE SATURDAY PAGE By Jim Hodge

Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 – 1995), Saturday 16 June 1979, page 17

Eventually I acquired a T-model Ford with as much character as any horse. In the end it had only one gear left – reverse. When it came time to pass it on to a new owner I delivered it backwards, with all the dust in my eyes.

Eventually I acquired a T-model Ford with as much character as any horse. In the end it had only one gear left – reverse. When it came time to pass it on to a new owner I delivered it backwards, with all the dust in my eyes.

Hello there , back in the 80,s we had a sheep station lake Stewart station , near Tibooburra.

We had jollities out back books out there and they were very good.. do you think you are going to bring them back .. into print.. thank you..

Hi, I am writing a paper on the fences in Jolliffe cartoons, and I would appreciate it if you would contact me. Thanks, John