Geared to unsheared beard

Two Hairy Subjects

A BEARDED WOMAN

Zenora Pastrana

In the Anthropological Exhibition recently held by Mr. J. B. Gassner, in Munich, was a bearded lady known as Zenora Pastrana, who affords a remarkable example of an extraordinary growth of hair (Hypertricliosis). Her mother, Julia Pastrana, was born in Mexico and married an American. She was covered all over, except her breast, with a silky coat of hair, which was longer about her chin, cheeks, and lips. She died in childbirth in Moscow, at the age of 31 years, in 1860. She and the baby (which was also covered with hair) were embalmed, and their mummies are shown in the same collection as the living daughter.

ZENORA PASTRANA

Is 29 years of age, and was born in America. She also married an American, who died in St. Petersburg in 1881. She had one child, who was not different from ordinary boys, but who died recently at the age of 7 years. Zenora is about the medium height, with a neat figure, but with a “manly” beard, which, unlike the hair growth of bearded women generally, is strong on the cheeks, chin, and upper lip. As a rule, these appendages in women differ from the hair growth in men in that they are what maybe described as patchy. A woman with a beard on her chin seldom has a moustache in proportion, and vice versa. In this case, however, the full beard is present, and is quite as strong as it is in many men. Madame Zenora is very accomplished, speaks several languages, and plays and sings charmingly. She is an enthusiastic dancer, and her movements are graceful and easy She is, moreover, very clever in all kinds of womanly work. This curious case of Hypertricliosis in the second generation has naturally attracted the attention of scientific men ; and numerous discussions have been held. But Madame Zonora can scarcely be considered as the missing link, or even an example of the homo ferus of Linneus.

Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 – 1907), Saturday 8 June 1889, page 28

MAN WITH A BEARD EIGHT FEET LONG

Another curious example of the extraordinary growth of hair is that of LOUIS GOULON, a native of Vandenesse, Canton Moulins-Engilbert, Department of Nièvre (France), where his family has been in the iron working trade for generations. He was compelled to begin shaving when only 12 years of age. But his beard grew so fast that it was impossible to keep it back ; and he gave up the attempt. At 14 he had a full beard 11in long ; and by the time he was 20 it was 39in long.

Another curious example of the extraordinary growth of hair is that of LOUIS GOULON, a native of Vandenesse, Canton Moulins-Engilbert, Department of Nièvre (France), where his family has been in the iron working trade for generations. He was compelled to begin shaving when only 12 years of age. But his beard grew so fast that it was impossible to keep it back ; and he gave up the attempt. At 14 he had a full beard 11in long ; and by the time he was 20 it was 39in long.

In 1878 a bearded Englishman was exhibited in Paris. The Englishman had a fine, well-kept beard, which reached down to the ground. Goulon, hearing of this, went to Paris, and showed himself. He had to carry his beard over his arm when he walked ; and the Englishman speedily retired from the field defeated, perhaps, though not disgraced. At the present time Goulon is 63 years of age ; and his beard (which was once a bright brown) has turned nearly white. But it has lost none of its extraordinary growth, as it is 2 metres 52 centimetres, or 8ft 33in long ; while Goulon himself is only 5ft 2in in height. When at work he winds it twice round his neck ; and it serves him as a breast protector. He has been offered large sums by British and American showmen and speculators to allow himself to be exhibited. But he has always declined, and is still a foreman in Messrs. Forey’s large iron factory, Montiuçon, department of Allier, the principal seat of the iron industry in France. Goulon has held this position for many years, and is respected by all who know him.

Rauber

The most noted examples of an extraordinary growth of beard are those of a German gentleman of the name of Rauber, of the sixteenth century, whose beard reached to the ground and back to his waist. He is said to have been very tall. He rarely rode in his carriage, but preferred to walk with his beard rolled round a baton, which he carried in his hand. When he died his beard was cut in two, and carefully preserved. A Russian gentleman is also reported to have owned a beard which reached to the ground ; and the ends were then tucked into his girdle. The Scythians were in ancient times noted for their beards ; and the Greeks and Romans used to speak of a man as being bearded like a Scythian.” Some very large beards are to be found to the present day among their Slavish descendants. But for length of growth Louis Goulon beats the record, and may be considered the world’s champion in this respect.

Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 – 1907), Saturday 8 June 1889, page 28

Speak with respect and honour, both of the beard and the beard’s owner.

[“Hudibras”, a poem by Samuel Butler, 166?]

- Towards the end of the eleventh century, it was decreed by the

pope, and zealously supported by the ecclesiastical authorities all over Europe, that such persons as wore long hair should be excommunicated while living and not be prayed for when dead.

pope, and zealously supported by the ecclesiastical authorities all over Europe, that such persons as wore long hair should be excommunicated while living and not be prayed for when dead. - Alexander the Great thought that the beards of the soldiery afforded convenient handles for the enemy to lay hold of, preparatory to cutting off their heads; and, with a view of depriving them of this advantage, he ordered the whole of his army to be closely shaven.

- the beard fell into disrepute after the death of Henry IV., from the mere reason that his successor was too young to have one.

- In the German newspapers, of August 1838, appeared an ordonnance, signed by the king of Bavaria, forbidding civilians, on any pretence whatever, to wear moustaches, and commanding the police and other authorities to arrest, and cause to be shaved, the offending parties. “Strange to say,” adds Le Droit, the journal from which this account is taken, “moustaches disappeared immediately,

- In the first year of the reign of Queen Elizabeth an attempt was made to add to the revenue by taxing at the rate of 3s. 4d. every beard of above a fortnight’s growth.

- A decree was issued by Peter II. in 1728 permitting peasants employed in agriculture to wear their beards. Fifty roubles had to be paid by all other persons, and the tax was rigidly enforced.

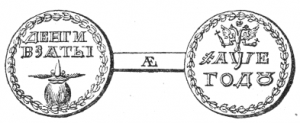

- During thirty-eight years in Russia, the beard-token or Borodoráia (the bearded), as it was called, was in use. As we write we have one of these tokens before us, and on one side are represented a nose, mouth, moustaches, and a large flowing beard, with the inscription “dinge vsatia,” which means “money received”; the reverse bears the year in Russian characters (equivalent to “1705 year”), and the black eagle of the empire.

Borodoráia

- It was customary among the Gauls to wash the hair with a lixivium made of chalk in order to increase its redness.

Before powder was used, the hair was generally greased with pomade, and powdering operations were attended with some trouble. In houses of any pretension was a small room set apart for the purpose, and it was known as the powdering-room. Here were fixed two curtains, and the person went behind, exposing the head only, which received its proper supply of powder without any going on the clothes of the individual dressed. A great deal of flour was used as hair powder, and an attempt was made to check its use. The following is a copy of a municipal proclamation issued at Great Yarmouth:—

Disuse of Hair Powder

Owing to the present enormous price of corn, and the alarming approach of a scarcity in that most necessary article, many towns throughout the kingdom have set the laudable example of leaving off for a time the custom of wearing powder for the hair; by which means a great quantity of wheat must infallibly be saved to the nation; and if the price be not reduced, it may at least be prevented from increasing. We, therefore, the Mayor, Justices, and principal inhabitants of Great Yarmouth, do recommend this example as worthy to be imitated; and we flatter ourselves the Military will not hesitate to adopt it, being fully convinced that appearances are at all times to be sacrificed to the public weal, and that in doing this they really do good.

W. Taylor, Mayor.

January 27th, 1795.

In the palmy days of wigs the price of a full-wig of an English gentleman was from thirty to forty guineas. Street quarrels in the olden time were by no means uncommon; care had to be exercised that wigs were not lost.

In the first year of the reign of Queen Victoria, we gather from the police court proceedings at Marlborough Street, London, how unpopular at that period was the moustache.

About 1855 the beard movement took hold of Englishmen. The Crimean War had much to do with it, as our soldiers were permitted to forego the use of the razor as the hair on the face protected them from the cold and attacks of neuralgia.

Mount Alexander Mail (Vic. : 1854 – 1917), Monday 10 July 1916, page 4

Longest Beard in History

The longest board referred to in European history is that which adorned the person of John Mayo, painter to the Emperor Charles V. It is said of him that though he was very tall his board was so long that he could tread upon it. Naturally he was very proud of his possession, and took such great care of it that he usually went about with it carefully gathered up into festoons, the points of the hair being looped up and tied with ribbon to a buttonhole of his coat. But sometimes, by the express desire of the Emperor, Mayo would untie his beard to its full length, whereupon his Majesty would command the windows to be opened so that the beard might have full play.

The Emperor took great sport in watching the wind blow this long beard in the faces of his courtiers

but the latter must have enjoyed dining with his Majesty much better when the artist was not present.

pope, and zealously supported by the ecclesiastical authorities all over Europe, that such persons as wore long hair should be excommunicated while living and not be prayed for when dead.

pope, and zealously supported by the ecclesiastical authorities all over Europe, that such persons as wore long hair should be excommunicated while living and not be prayed for when dead.